Mor magnai—Sewing the Mola

Report from the Memoria Indígena annual gathering, Panamá 2018

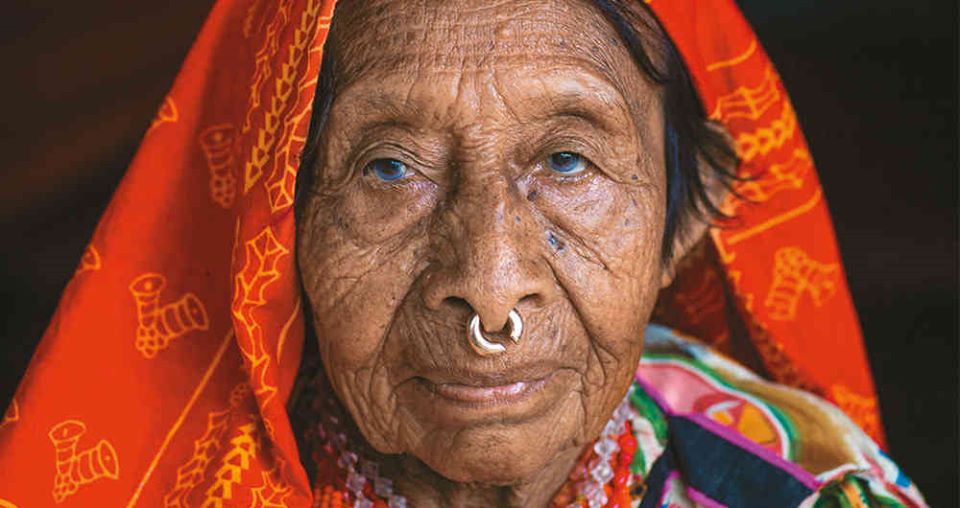

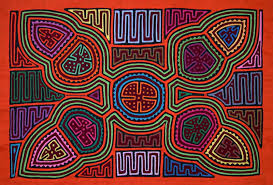

The weavings of our Indigenous peoples are memories that speak to us of the millenary experiences and life of our peoples in Abya Yala (This is the name by which the continent called America is known, which literally means “fully mature land” or “the land of vital blood”). The memories are created through the dyes extracted from the fruits of plants, from the skin of animals such as wool, from human creations such as thread and needles, as well as other elements, all which show us the strength of our identities. One of the fabrics of the Gunadule nation is the mola (textile art and form of communication of the Gunadule women). We desire this design to help us acknowledge one of the wonderful ways that the Gunadule people have sustained their memories. And by way of the metaphor of the mola we would like to share the experiences, challenges and proposals that came out of our gathering between Indigenous Pathways and Memoria Indígena on the islands of Senidub, Icodub, Moraggedub,Gaigirgordub in Guna Yala, territory of the Gunadule nation. In this process we are not just a passive needle, rather we are threads and needles that are united with the great designer who is our Creator, and as we unite our threads of many different colors we continue to create new designs. Without a doubt this is what Memoria Indigena is made of–a collective creation where all are invited to weave and in this weaving we continue remembering and looking with hope at that which the Creator is sewing in the peoples of Abya Yala.

The weavings of our Indigenous peoples are memories that speak to us of the millenary experiences and life of our peoples in Abya Yala (This is the name by which the continent called America is known, which literally means “fully mature land” or “the land of vital blood”). The memories are created through the dyes extracted from the fruits of plants, from the skin of animals such as wool, from human creations such as thread and needles, as well as other elements, all which show us the strength of our identities. One of the fabrics of the Gunadule nation is the mola (textile art and form of communication of the Gunadule women). We desire this design to help us acknowledge one of the wonderful ways that the Gunadule people have sustained their memories. And by way of the metaphor of the mola we would like to share the experiences, challenges and proposals that came out of our gathering between Indigenous Pathways and Memoria Indígena on the islands of Senidub, Icodub, Moraggedub,Gaigirgordub in Guna Yala, territory of the Gunadule nation. In this process we are not just a passive needle, rather we are threads and needles that are united with the great designer who is our Creator, and as we unite our threads of many different colors we continue to create new designs. Without a doubt this is what Memoria Indigena is made of–a collective creation where all are invited to weave and in this weaving we continue remembering and looking with hope at that which the Creator is sewing in the peoples of Abya Yala.

Nermagged (Draw)

So that the mola design is full of contrasts, lines, curve, figures and geometry one must make a good design. These sketches help the mola to take on life and presence as it is sewn together, revealing the design of the artist.

A few years ago as Memoria Indigena we decided to approach NAIITS: An Indigenous Learning Community. Little by little we began to draw the route for this journey. We went to the symposiums that they hold every year and there we began to develop relationships with Terry LeBlanc, Shari Russell, Gene Green and others. We pray to God that this weaving we be strengthened because we know that one alone can easily be defeated, but two can hold. The cord of three strands will not break easily (Ecclesiastes 4:12)! God opened doors to deepen this relationship and God did hear our prayer. God with his needle brought together threads that he put on our hearts to dream, weave, and paddle.

Some of the threads that gave shape to the design of the mola were questions that participants brought to our gathering. How does the good news of the good purposes of God revealed in Jesus Christ dialogue with the the memories of our peoples in Abya Yala? How does the Indigenous person follow Jesus? How do we recognize ourselves within the mola of the stories that our communities share by way of the Spirit of Life? How do we hear and see the presence of God in the narratives of our ancestors? What have been the contributions of our Christian Indigenous leaders to their communities from their faith in Jesus? What is God’s heartbeat for the peoples of Abya Yala? How should we walk together as Christian Indigenous organizations who recognize the importance of strengthening community? How conscious are we of the colonialism that ferments the masses of our peoples and which often wears the mask of religiosity and carries the flag of Christianity? These questions and reflections, among many more, helped us to have a deep, sincere, transparent and truthful dialogue, as well as carried us to specify and propose new designs for our mola from a place of communal creation. We want to share some of these threads with you below.

Some of the threads that gave shape to the design of the mola were questions that participants brought to our gathering. How does the good news of the good purposes of God revealed in Jesus Christ dialogue with the the memories of our peoples in Abya Yala? How does the Indigenous person follow Jesus? How do we recognize ourselves within the mola of the stories that our communities share by way of the Spirit of Life? How do we hear and see the presence of God in the narratives of our ancestors? What have been the contributions of our Christian Indigenous leaders to their communities from their faith in Jesus? What is God’s heartbeat for the peoples of Abya Yala? How should we walk together as Christian Indigenous organizations who recognize the importance of strengthening community? How conscious are we of the colonialism that ferments the masses of our peoples and which often wears the mask of religiosity and carries the flag of Christianity? These questions and reflections, among many more, helped us to have a deep, sincere, transparent and truthful dialogue, as well as carried us to specify and propose new designs for our mola from a place of communal creation. We want to share some of these threads with you below.

Mor binid (New mola designs)

The art of designing the mola emerges from the experience of facing new challenges. The artist begins to create and recreate new styles that permits her to enjoy new pieces of fabric.

From the moment we entered the territory of the Guna nation, Guna Yala, the social and economic order we observed began to generate questions. We pulled up to the checkpoint to enter this autonomous territory. Without a doubt, in order to generate their own economy like the one we were looking at and to achieve this level of independence as a nation they have been through a long process that has historically involved confrontations and dialogue with the State. Despite everything, it is amazing that on a continent where government structures and politics are designed to work against and reduce the poorly-named “ethnic minorities,” the Gunadule have learned to adapt local politics to their favor and have thus been able to guarantee their permanence.

One result of the Gunadule’s autonomy has been the preservation of their beaches and mountains in the face of a “progress” that devours and dominates creation. At the same time their resistance to disappearing and their constant search for responses to new cultural phenomenon without leaving behind the conservation of their own cultural expressions is evident. Here, despite so many struggles the Gunadule continue taking the strips of cloth they have and transforming them into new figures to show to the world, such as the case of their appropriation of ethnotourism.

With our first steps in Guna territory we were enveloped in its cultural and natural richness. And it was with these first experiences that we already began to make new memories based on our own curiosities and observations that invited us to want to know more, not just of the Guna ways of life but beyond that to discover more deeply who we are as people belonging to other Indigenous nations. So this gathering motivated us to learn as Indigenous peoples: walking, thinking, saving, conversing and conserving.

Our gathering on the island, like the migratory birds which that same time of year gather on these islands, allowed us to pause and reflect, exchange, and continue our journey in community. Just like the birds that arrive from here and from there but all share a common home which we call mother, beginning with our devotional space we began to feel and listen to the voice of that mother that sustains us, the voice of God that surrounds us manifested itself in the Caribbean breeze. The sea sang its song and the Spirit was present as we sang an Aymara hymn, “No Turning Back” —a spiritual song and memory that gathers us an reminds us of the struggles of our Indigenous Bolivian brothers and sisters, when the hacienda owners hoarded their lands and this song gave them inspiration to continue journeying and dreaming. From this beginning we had already begun to weave together our mola, outlining drawings and expressing a story.

Memory and Dance

Our stay on an island gave us the chance to grow closer to our other brothers and sisters, however it left us want to immerse ourselves more in Gunadule culture, in their daily life and relationships. Our visit to a habited Guna island permitted us to feel strange ourselves—a feeling which establishes that we are different although we share a same spirit and dance, which we gave back in gratitude for our visit.

An island is like a communal house; the school, the family homes, the congress house and the chicha house. Each one give order and sense to the community. This is the case with the Congress House. As we enter they ask us to do so with reverence, concealing our amazement and repressing the impulse to take photos, in order to open up our imagination to the expectation of the world that that the Saglas and Argars open for us. These are the authorities in Guna communities that know the laws, treaties, and songs that are as old as the ancestors. In the oral stories that the Guna tell through the Saglas, they narrate the history of their colonization, their resistance, the forced removals, and the colonizers’ thirst for gold.

The Congress House is the highest expression of memory and narrative. Here is where the memories not found on paper nor in photographs remain alive, and in this sacred space is opened a world of interpretations. Hammocks are hung, some to sing and others to interpret the song. They invite us to feel and receive the breath of Nana, heavenly mother because the community rests on their ancestral stories and at the same time their narration allows them to protect, adapt and continue their identity. From this place they bring to memory the ancestors’ blood spilled and out of those painful experiences they look for reconciliation, peace and unity.

Memory and Reconciliation with Our Identity in Pastoral Work

One territory and one people does not mean there is just one identity or faith. Having recognized this, Christianity is one of the diverse spiritual forms that share the territory of Guna Yala. In this specific context the Baptists are the denomination with the most influence in this paradise. Their presence for many years has open doors for them to participate in the culture and tradition of the people.

However, this call to make community with diverse forms of faith expressions has constantly caused encounters and disagreements between the Christian faith and ancestral faith. But despite everything, on this walk between the Christian faith and the ancestral forms paths have come together. Pastors and traditional leaders have broadened their thinking and the possibility of building community together, so that now it is possible for a pastor to take on the role of Sagla, which some others possibly still see as an act of betrayal of the Christian faith. As visitors and learners in the Guna islands, it is revealing to come to understand that the gospel we profess needs to be found in the path of the ancestors and that possibility contributes to the values of the community.

More than just enjoying a traditional Guna meal, in this space with the local pastors we could discuss the challenges Indigenous pastors face in their dialogue with the community and their responsibility towards their identity in the midst of a social context where a large part of these communities migrate to the cities.

In this exchange we understand that conversion is not only about the gospel to which we must convert, rather it is also necessary for us to convert to the culture. This is the case of a promoter of Guna music and culture that we met, Yobani, who after growing up in an urban church context has gone through a process reconciling himself with his culture and identity. Hearing his testimony we must begin to understand that many who renounce their Indigenous identity do so because of the discrimination they experience, as well as other related factors that do not help guarantee processes for Indigenous Christians to reconsider their faith from their culture.

Even so, the step the Baptist Guna pastors have taken is important since they have been able to connect their roles within the communities and in one form or another are considered trustworthy. For now the communication of the gospel continues along with the emergence of new social problems such as drug consumption among the youth—a reality which has undoubtedly touched many other Indigenous communities.

We also realized that to speak of Memoria Indígena implies that we must dialogue about the roles and processes that we must take on in the face of possible crises within Indigenous communities because a church conscious of these realities will allow them to testify to the gospel by showing a deep concern for understanding the changes that are approaching that community. As a consequence of these exchanges there grew within us an interest in continuing to refine our program according to our Indigenous vision. It was like an act of healing to consider how our notion of time, horizontal dialogue, sharing, ocupying diverse spaces, observation, and even dance and song as possibilities for remembering a darkened past and making memory from them. For some participants this gathering meant an opportunity to reconcile ourselves with our Indigenous identity, for some it was the opportunity to begin a journey, but in general it was the possibility to build a solid and deep friendship that helps us to respond effectively to God’s big dream.

As the hours passed together our time was filled with encounters and reencounters. During our conversations, laments and celebrations we felt a profound connection between these friends from South, North and Central America where we could transparently share our struggles and longings. We believe that this moment was a big step for us to continue sewing our mola together, guided and accompanied by the Spirit in our desire to follow the Lord of the cosmos out of our own identities.

One of our friends, Diwar, expressed his fears in these terms: “What happens when a church or denomination goes to the extreme in an Indigenous context? In some cases the churches demand that the Indigenous person be sinless, but what happens when they do this? Especially in cases when they do not permit any processes for restoration. We Indigenous peoples are almost always located in contexts where there are constant clashes between different churches. Many of these churches when they arrive tell us, ‘the Spirit gives life, the letter kills.’”

We understand the worry of our companion and friend, Diwar. Indigenous peoples have been immersed in an evangelization project where we are almost not allowed to think, rather they see us as individuals ready to receive, to the point that they even question our way of being Indigenous and our way of celebrating our faith. Gene Green, one of the representatives of NAIITS, said it well in one dialogue time: “The letter that kills is the one that does not give life, the law that was made to repress. These evasions happen often because of a lack of good study of the Word that can contribute to life.”

In this path of making memory we need certain processes of formation and participation in the local community. There are always initiatives out there where the Spirit of life turns to the minority. The growth of NAIITS has not been the exception where we see that for more than 20 years they have learned to challenge others in a world where there is little room to rethink our roots, where the tendency from any vision has been to repress the Indigenous person. But this path they have taken which many have questioned or judged from their perspectives has open doors in many places. On occasions the path forward has been possible but on others there is much resistance to their calling. In the midst of this they have not stopped contributing from their academic and life spaces.

For Shari it is vital that we concentrate our energies where we find echoes in our dialogue with entities and organizations that are open to our vision. There will be places where the doors will close on us and there we must simply shake the dust off our feet, since there are places where the power of evangelical denominations or institutions has much influence. Some have chosen to accuse, but none of this means we should stop trying. Our fundamental value must consist of the capacity to listen to one another. Many times this means we must be willing to invite those who condemn us to the table. It is not possible to waste our efforts on these institutions because while many times the institution may not be able to change course, there are people within them that do have the ability and desire to contribute to our project. This is one of the reasons that moves us to approach those institutions that seem to have a vision that is distinct from ours.

Shari reminded us that these initiatives are long-term processes, like Terry who has been on this path for almost 30 years. We can say, then, that Memoria Indígena has begun its journey and those of us who are here are part of this process. Some have gone, others are arriving, and others have been constant, just like the live of the NAIITS community.

We could take note that NAIITS is fruit partly of this persistence, but others who are not have also contributed to and received from this process in a reciprocal way. For example, as a participant in this cooperation, Gene remembered being questioned by other Christians who considered Native ceremonies and pipes in the church as syncretism.

Ruth Padilla Deborst also shared with us in this brief historical review abou the emergence of the Latin American Theological Fellowship (FTL). She mentioned that it grew precisely in this search and questioning of hegemonic forms that came from the questioning of a group of friends interested in contributing to theology from and for Latin America. Although many labeled them as unchristian, their proposals grew in strength. The emergence of the FTL is a clear testimony that many theological expressions and searches should come out of the land that we walk on.

Memoria Indígena has been forming a friendship where ideas are able to ferment. As we can express from a Guna perspective, we have been interweaving a great mola that attempts to capture our theologies, memories, stories and biographies, cultivating community according to the visions of our Indigenous peoples of Abya Yala and the revelation and truth of God. In this sense we think it is good to dialogue with groups like the FTL and NAIITS and their contributions, without wanting to remain centered on their work and discourses but rather with the desire to nurture our community and movement with their experiences onthis pilgrimage.

In those years those who would later form the FTL laid out a simple question: Why do others have to come in from the outside to tell us what to do and think? What do we want to share? What can the things we have learned contribute to our real context? How do we do contextual theology? These are the same things that we wish to address, but now from the context of Indigenous churches in Abya Yala.

Bular imaileged (Community creation)

Three women intervened in the creation of this art form: Inanadili, who was the first to teach the women to use bird feathers for their dresses and create the first designs. Kikadiryai, who introduced the use of cotton to create thread and plant-based dyes to bring color to the molas. Finally, a third woman arrived, Nagediliyai, of whom it is said was the first woman to perfect the creation of the mola.

Throughout the event all of us participated, sharing our ideas, experiences and dreams. With the contribution of each we created together and these themes began to emerge:

Strengthen our Community

A strong theme was that we need to focus more on our community and companionship. Both within the Memoria Indígena community and outside we desire to create deep connections of friendship with other people and institutions such as Indigenous Pathways. In the same way we will continue to promote more exchange between communities and churches in order to strengthen our ties of fellowship and learn mutually from one another.

This theme also implies our desire to celebrate our identities more when we do gather together through our memories, art, music and dance. Furthermore we want to continue supporting local initiatives where we can accompany our brothers and sisters in their own contexts.

Here we mention some of the ideas our team discussed in order for us to do this:

- Do a better job of feedback and follow-up with people who participate in our events and demonstrate much interest or ability. We want to invite them to walk with us and stay in contact.

- Communicate amongst ourselves more frequently. As a team we need to talk more not just about our work but also seeking to strengthen one another in our spiritual lives and in our search for our calling and dreams.

- Create a list of themes and areas that we as a coordinating team need to talk about and develop.

- Create another list of topics that we are interested to research more that we can begin to work through together and with others through virtual platforms. These are areas we wish to develop to strengthen our theological and methodological roots. Ismael shared that he would like to facilitate these spaces and conversations.

- We need to look for other people who can act as our “elders” in this movement, especially other Indigenous people from Abya Yala. Although some could be Natives from North America that have walked longer on this path and others could be Latin Americans who have experience working in the areas of contextual theology, integral mission, theological education and formation, and writing.

Produce Theological Reflection

The second principle theme dealt with the need for an Indigenous Christian formation and education. In our communities and churches there exists a deep desire to broaden our theological, biblical and pedagogical knowledge, but from our own Indigenous realities and world visions. Also within our own Memoria Indígena community we have the desire for more formation in order to be better equipped to form others in this journey of decolonization of the Indigenous church and critical contextualization of its practices. NAIITS’s example inspires us to together explore more about how we can accompany and shape Indigenous leaders who desire to cultivate their relationship with Jesus and form churches with a profound Indigenous identity within their communities. We feel that the task before us requires us to develop tools, materials, platforms and courses with Indigenous methodologies and epistemologies to train our brothers and sisters in Abya Yala who will continue contributing to the Kingdom of God among their people and beyond. Here we note some of our main questions from our conversations:

- We want to create a database of people, institutions, programs, books and other resources that we can suggest to Indigenous youth that share our concern and vision for the Indigenous church and desire to grow and equip themselves more to better work on these themes in their own contexts and with their communities. Perhaps this list will not have too many Indigenous people or institutions that teach from an Indigenous paradigm but we hope to discover more and create such spaces.

- Relate to this database, we need to create a more complete list of contacts with people and institutions that have helped us or offered to help or shown interest in supporting our vision.

- How can we begin to identify key people who we want to support so that they can get better formation? We need to help create a group that can lead in the creation of Indigenous programs based on Indigenous pedagogies. In the meantime we need to accompany those who are currently being trained because the theological education offered today is not from an Indigenous perspective. Or we could help them learn English so they could study with NAIITS. We also need to look at how we can raise funds to create scholarships.

- We must promote the publication of theological reflection on our website.

- In this area, as well as in the area of producing biographies, we need to train writers who can also equip others to write.

- We have to think more about how we teach and learn.

- We need to begin to together create resources to share with others who want to reman and serve in their contexts, like a toolbox.

Based on these themes and others, together with our friends from Indigenous Pathways/NAIITS we thought of some initial steps we could take to create together this new mola design. We were challenged to see how we could start from our exchange of experiences and ideas to continue strengthening our relationships. The following are some of the ideas for action we came up with:

- Exchange of participants at the annual gatherings of NAIITS and Memoria Indígena. We can send people to participate at the NAIITS symposium and they can send some to our gathering. The difficulty here more than anything will be obtaining visas to the USA or Canada. For that reason, we propose to NAIITS that they do their annual symposium in South America one year.

- We wish to invite people from Indigenous Pathways to participate in our workshops in Indigenous communities.

- Send a family from Memoria Indígena to the Wiconi Family Camp/Powwow.

- Translate more books written by NAIITS authors into Spanish.

- Ask NAIITS to provide us with documentation on the development of the philosophy and pedagogy of their academic courses and programs which can help us develop our own courses and programs.

Working on the mola requires knowledge of art. It is an interconnection of a mix of knowledges that have their home in the Gunadule community. Participation in this elaboration entails relationship with the land, with the memories expressed in the songs, narratives and symbols of the Gunadule people. It is to live an experience that permits us to know ourselves and know the other from their diversity, put it also permits us to open up and walk in the path towards Bad Igala (path towards God) as it is called in Gunadule spirituality. It lets us reimagine designs of hope and justice for the peoples of Abya Yala. As we have already expressed, we recognize the most important thread that brings all together in the sewing of this mola is the grace of Jesus shown to our peoples, manifested in his good purposes, which the memories in the Bible sing of in the Psalms, particularly in Psalm 136. In this Psalm the chorus repeats 26 times “For his lovingkindness is everlasting!” This short phrase reminds us of the great things God has done to favor his people.

As Memoria Indígena we praise God with gratitude for what he did in Panama. We celebrate the acts of God in the memories of the peoples of Guna Yala, Abya Yala, all over the world, in our lives, and in our gathering. Thank you for also being a part of this weaving, where each colored thread unites to form the momoll (the word that mola is derived from, which means butterfly). It is in this metamorphosis of life that we recognize that God is intervening with her needle and forming new designs. We give thanks to the Lord because he is good. Because his lovingkindness is everlasting.

Memoria Indígena writing team,

Ismael, Juana, Jocabed and Drew

Apendix

Pagamento, or spiritual contribution

During the Memoria Indígena gathering in Guna Yala an ancestral practice of the Indigenous peoples of the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta was recalled. This practice consists of a kind of spiritual payment as a demonstration of respect to the inhabitants of a place. The payment consists of recording one’s thoughts in sacred places, making a memory of what thoughts one had along the way, both good and bad thoughts. The act involves bringing these thoughts to this place and leaving them there as a way of feeding the place, while at the same time it is a way of asking permission of the place to be there.

In Guna Yala we adpated this practice as a methodology of collective participation, so after time of conversation, excusions to other islands, a devotional time or other exposition, each participant was asked to leave a thought on a small piece of paper in a bag left in the center of our circle. In an effort to reflect the diverse voices and feelings of all the participants in this document, the following is a transcription of all the thoughts contributed as pagamentos by each participant in the Memoria Indígena gathering, Guna Yala, Panama, 2018:

A new mola design can be sewn when new colors and fabrics are added. Our theology should be woven in community.

Is the community the church?

As Marcelo said, we need to acknowledge those who have come before us doing the work of contextual theology.

Our journey grows when we work and walk together. The center is greater than each one of us (with a drawing of a spiral).

Work and dream together

We came as friends, we left as family

Community is created around food.

The Medicine Wheel: When all the colors and directions come together there is healing-wholeness for the church, communities and individuals.

Is the church listening? If not, we are.

How do we keep community at the center?

The community is the place where life happens. Theology also is born from the community. God is theologizing.

The church should not define or restrict who we are as Indigenous peoples, rather it should bring freedom.

There is a need to be strong, rooted, so that we can participate in the wider conversation with confidence.

There is a rich cultural beauty and history and connection here that is a treasure that should be shared with the world. We will be richer in our knowledge and experience of God when this treasure is shared.

The process is different for each community and person. It is important to show grace to yourself and to others in the process.

The dream of hearing the voices of our elders and ancestors—the theology that was born from within our own people.

We are stronger together.

The voice of the woman—the Indigenous woman—is integral to our community.

The Creator is doing great things with each one of us.

Be strong in who you are.

Our questions and conversations will carry us closer to the Creator.

Let’s build a brotherly bond, a huge family of solidarity, complementarity, and reciprocity with more and more generosity.

A feeling of harmony and love.

If you want to go quick, go alone! If you want to go far go together!

Identity- the role of Indigenous and Christian education to affirm it.

Circle of life

To listen to our elders’ counsel is to learn to live.

To live in the present and the future, we must live thinking of the past. Spiral.

Our global Indigenous family is the expression of our Indigenous church.

Not only writing, we also need to sing to tell our story because song heals.

The Lord will give us strength, the water here is like the tree of our land. Isaiah 61.4

Work together, be supportive, take opportunities, be a grand family where it is possible to make things smoother.

Every people is particular but we also have much in common as human beings.

Unity: an important factor for growth.

Music, narrative, histories, dance, art are all an integral part of the Indigenous person, but the spaces where these things are done are much smaller now.

Celebration unites and reunites people. When we celebrate who we are and give thanks to the Lord, the world listens to us.

To acknowledge and appreciate the Heart of the People is a work of the kingdom of God.

Is it possible to become authentically Indigenous and authentically Christian?

We must think and get out and search for a more integral and Indigenous education that echoes the nations from north to south and motivates Indigenous organizations.

In the Indigenous world we need to know God as manifest in our culture.

We are small and few. Thinking about creating a movement like this sounds good but sometimes I feel very small to be able to do it. Sometimes I feel like is tour efforts remain small that is fine, but if it does grow that is good too.

God is diverse. When I see the deep waters, the sea, I see the characteristics of God. His love is immense and deep.

How do we approach our Indigenous elders today, so that they can guide and teach us?

Friends seeking to walk together, but how do we do it over long distances?

Memoria Indígena needs a structure that reflects the identities and the vision that it has, not copy other structures nor be sloppy or irresponsible.

Memoria Indígena needs a structure that helps distribute roles.

To build on what has already been built, connecting with other organizations and communities. To be equipped to give voice to what we already have inside.

To share friendship between cultures

AMIGO

If God Almighty has us here it is with a purpose of doing great things.

God is a multicultural God.

One’s identity is a voice that emerges from the deepest parts of the heart.

In the heart of any reform there is a group of friends that pray, cry, struggle and explore in community.

Unity is important and fundamental on this journey. We build together.

Aproximarse a la creación de la vida presente en la plenitud de la naturaleza es ver el rostro de su autor.

This relationship with NAIITS should continue but our hope and solidarity should be first in Jesus and we should first begin working where we are, later spreading out.

Is the relationship with NAIITS changing Memoria Indígena, from focusing on writing histories to educating?

To motivate leadership and integral Indigenous community through theology and biblical viewpoints in our Native continent.

Listening to others give us discernment to walk together well.

How to draw out of ourselves and create works of art that speak of our peoples.

The Indigenous voice is a gift. God is for all peoples. The wellbeing of all the peoples of the Earth, our life, depends on listening to it.

I commit myself to accompanying my Indigenous brothers and sisters of Abya Yala to articulate and express their stories and theologies in writing.

It is time to talk about ethnic Christianity, something that has been viewed poorly. Many people who have not been in favor of this phenomenon have preferred elimination before learning of their contributions and faults. But recognizing that other faith expressions do exist in Indigenous communities is to want to cultivate community.

We must dialogue more on this idea of reached and unreached.

Why should we keep trying to work with foreign institutions? Why not reimagine the Indigenous church as an integral part of our local community?

What does it mean to be the church?

The church needs to take up its Indigenous face in Spirit and in truth.

A church that creates opportunity and hospitality

Community church

What is CETI’s role in this?

Speak the truth in love, without fear. Seek to include, but do not keep insisting with those who reject us or do not want to accept us on our terms.

How do we find more women?

We all have an origen to tell about. Our surroundings evoke that origen, our life evokes that origen. The big dream (vision) takes shape organically.

Jesus the whole and Indigenous light.

We have so much to contribute to our leaders in the Christian church in order for our culture to survive.

Value all experiences to take the best from them. Help strengthen the nation through collectivity, solidarity between those of us who have come from a common story.

If we lose our native language, if we stop using it our culture will start disappearing, as well as our worldvision.

Listening to the stories of our Indigenous brothers and sisters here and hearing them speak their native languages, I understood that God was the first to speak in Native languages.