Narratives as Political Resistance: The Guna Experience in Panama

By: Jocabed Reina Solano Miselis

“The ancestors built their huts, they had good huts, but without order, without the compact forms of what we have today. Then Ibeorgún taught the elders to build better huts, to better define all the parts that make up the hut, to give them each an identity. The pole that you put in the center of the hut they called buwar[1], solid, straight, hard to rot, too heavy for one person to lift. Uusor[2], they called the pole where the nagubir [3] rests on each side. The other poles that permit the central pole to really be the buwar they called baggu,nagubir[4]. These lesser poles hold up and sustain the buwar, making the whole hut solid. The strong pole must hold itself up by the smaller ones so that the stoutest gives its strength to the weaker ones at the same time that it gains its vigor and stature from them. The poles speak to one another. The strong pole, the powerful buwar, says to its pole friends: “I cannot do this alone. I cannot hold up the weight of the hut alone. I am strong but you are the ones who give me your resistance and flexibility to hold up the hut, the whole house, so that the wind cannot blow away the hut, so the earthquake will not smash it, which is why I need you, dior, [5] even though you are the smallest. I need magged[6] to help me, my friend saderbir must also give me a hand. We all need the hand of the other. Only the union of our strength will make happy those who will sleep underneath us. I give my hand to dior; it in turn gives a hand to magged; magged offers its spine to saderbir[7]; and in that way we all give each other a hand. We all need sargi[8], the sargi will unite us so that we don’t each go our own way. We strong poles need the smaller ones. When we are all united by the sargi, the great bejuco (a vine), when we feel we are stuck together, we have the capacity to hold up the weight of the sosga, which covers our bones. We cannot permit that one alone carries the weight, even though it may be the strongest. United we must defend ourselves against the aggressive wind and the earthquakes which will shake us. The house belongs to all of us who lend our shoulder to keep it firm.”[9]

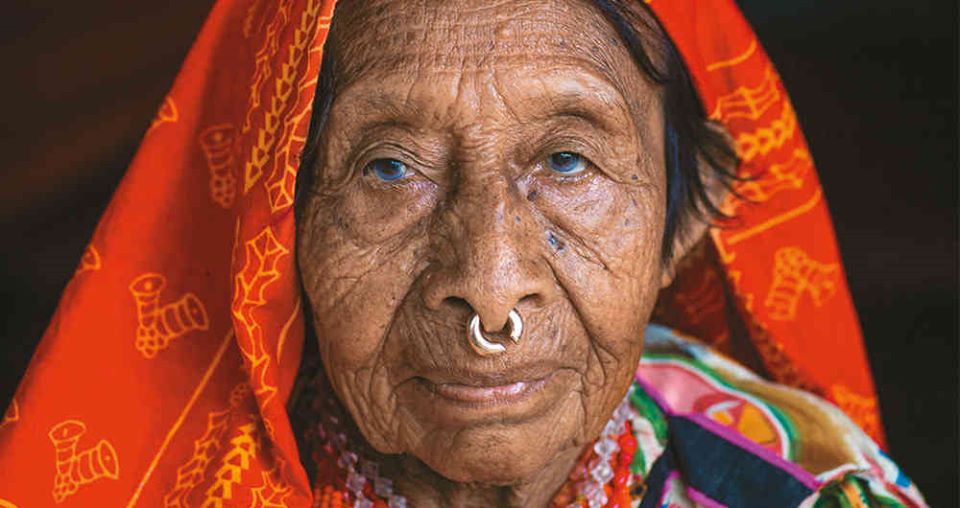

The Guna nation is a people of poets. Life itself is lived through narrative and poetry. Full of color, images, symbolism, contrast, imagination, magic, astonishment, perplexity, hiddenness, mystery, feeling. . . they evoke songs which are sung from generation to generation through time.

In a congressional meeting house, you can hear the song of a sagla (Guna leader) in their hammock singing about our social and political origin. From the smallest ones to the oldest adults, all go silent when the great leader begins to narrate the collective and ancestral memories of a people who have stayed firm in the midst of so many adversities.

Narratives as Political Resistance

The memories of our people sustain our sociopolitical organization, giving us sense and identity. Their interpretation and how we relate them to the world is based in our spirituality. This collective imagination that has taken shape little by little over generations from each historical moment, such as the struggles and revolutions of our people, has been important in the construction of our cosmic vision.

In this sense our narratives play an important role, as political resistance. Our stories matter and they are not taken in vain but are considered a sacred memory. They help us to analyze our self and how, in relation to the world that we live in, we have participated from a position of dissidence in the construction of society. At the same time, they internally shape the very constitution of the Guna being, which we recognize is a vocation we have received from the Creator.

Abya Yala, since the time of its colonization, has been beaten by prevailing hegemonic ideologies from the West. So, we must ask, in what ways have many Indigenous peoples resisted these threats? With this question in mind, I would like to propose that one of the forms in which the Guna nation has done so is through its narratives.

Guna narratives are present in every aspect of Guna life. The leaders, when they give counsel to the people, utilize their songs as a way to créate conciousness about the reality in which we are living, based on the anscestral songs which have a deeply social connotation. These narratives have strong elements of symbolism which relate to the mother earth and how interdependence in harmony between living things constitute an important part in the development of a people. The images they use are so impactful and described in such a detailed manner that they although use no tangible visual aids, and the listener easily develops the capacity to recreate his or her own images which remain burned into their daily life because they use figures, histories and elements that the Guna commonly uses. Thus, when we see those things in our home or work, we remember the story with which they are associated.

The stories also have the power to remind us of the collective memories of the ancestors by utilizing repetition, which from a Western viewpoint, may seem to be vain repetition, but each repetition adds a new ingredient, which makes you pay attention to find out what is going to happen. This is where the astonishing and mysterious come into play, adding new elements which créate new alternatives to be able to see and live life.

The narrator becomes united with the one who originally narrated it and the listener dialogues with the one who narrates. Where we narrate from is important in the Guna narrative because one narrates from the origin of the story and, even though we live in another time, this permits us to travel through time and connect directly to our grandfathers and grandmothers. This moment is sacred, because the Guna people know that a sacred story is being told which has the power to transform the world.

The purpose of storytelling is not entertainment, rather it is a purely political and religious act. Stories are told so that new generations do not forget where we come from, how we have walked through time until now, the struggles of our grandparents, and the importance of our identity as a signal of resistance in a society that wants to impose its norms for living life. In the background we hear this expression: How do I tell you in such a way that you will not forget? These stories have profoundly spiritual elements and not just anyone can tell the story, rather the leaders who have been prepared in the knowledge and wisdom of the Guna education tell them. They have studied the treaties, the songs and the symbols. They know the language of the wise ones, as well as, the knowledge related to mother earth, natural medicines, and other things.

However, it is understood that the narrative is being interpreted both by the one telling the story and the one who listens. The listeners are not passive beings because they are people that have a transformative function in the place that they live and coexist with the symbolical Guna pluriverse. That is to say that the autonomy of each listener is dynamic. The listener is invited to listen and realize the story in their own life. An example of this is when they tell the story of Duiren, a young man who taught the Guna people strategies to defend themselves against the external threats that they experienced. In this song, which begins from the childhood of Duiren and continues through his adult life, one can see in detail how the Guna people have been maturing in the theme of the defense of life. When the sagla sings the song, he says, “And now you, sons and daughters, today are called to be like Duiren, to defend yourselves utilizing the strategies received from our mothers and fathers in the midst of the threats of globalization, climate change, capitalism, and those who wish for our identity to die. Do not let the Guna spirit die, rather let us live as those who know who we are in this land of Abya Yala.”

Narrative among the Guna people is the foundation of the construction of the Guna hut, which is our Guna politics.

Building the Hut

For the Guna people, politics are rooted in daily life, submerged in the questions of basic necessity, like, where we are going to sleep? what we are going to eat? how we relate to one another? how we care for mother earth? So when we think about the building of a hut, our thinking moves beyond just the temporal moment and the act itself to how our method of building the hut is related to something greater—how we all are part of the Great Hut, the cosmos. From the relationship between our hut and the Great Hut one can see the spirituality that is manifest in our social and political organization.

Hut, in Guna, is called nega (house). But when we speak of our political organization, the word is transformed into onmagged nega, onmagged meaning to gather together. The two words together mean House of Congress.

“In the beginning our grandparents built huts, good huts. But they were not well-ordered like the compact ones we have today,” goes the story. This story about how to build a hut helps us to see beyond the hut, widening our vision which was given to us by Baba and Nana (Creator God/Goddess).

Time passed, and our organization matured. This momento of deepening of Guna politics is realted with two charaters, Iberogún and Gigardiryai.[10]

“Ibeorgún taught the ancestors to build better huts, to define each part well, giving them each an identity.” In Guna political organization, the phrase Ammar Burba Emarbi Niggad, can literally be translated, we are of the same Spirit. This means that our fundamental selves, who we are, where we come from, how we relate, what our values are, the purpose of our existence, and many other questions emerge out of our thinking about how we organize ourselves.

Then Ibeorgún began to show them how to build the hut, from a sense of community, where each part of the nega is very important. There are differences between one pole and another, some are stronger than others, buta all are important. The nega would not exist without the presence of the smallest part. Therefore, each participant in the Guna people is essential for making decisions.

This interaction and dialogue between one another is a sign of understanding the value of maintaining our circle. Because if we work together like our nega, also the animals, plants, and the earth are part of the equilibrium between us all as sons and daughters who coexist in the Great Hut which functions by a political system that we observe and learn from.

To build the hut we do not only need the materials that it is made of, rather we also need other elements that the communitarian system provides. This is where I would like to engage with this political construction from the viewpoint of Giggardiryai.

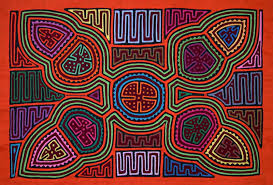

Weaving as political creation

“The great grandmother Giggardiryai also taught our ancestors to weave hammocks, and she went about naming them according to their use, size, and design.”

Our organization is both external and internal and both are interconnected. As this organization matures, each member of the community is strengthened. As dules, “living beings,” we are each individually invited to participate in our community. Thus, it is important to understand each aspect of daily life as a political act.

The hammock is the heart of Guna culture. It is where the wise ones sing, but it is also where each Guna sleeps and sleep is very important for us. When one wakes up in the morning, the question you are asked is, “What did you dream?” The great grandmother taught us to weave the hammock and without weaving the hut would no longer be a Guna hut.

In this moment, narrative is beginning to gain strength in our community, the integration of which is expressed well in our weavings. This is known as “ammar daet” which literally means the behavior, attitude, or way of being of the Gunas. These give life and permit connection between members of the community. This narrative connection is generated through our senses.

The Senses as a form of political communication

“The poles speak to one another. The strong pole, the powerful buwar, says to its other pole friends: ‘I cannot do this alone. I cannot carry the weight of the whole hut by myself….’”

In the West, the articulate use of words is important in politics. The more one talks, the better chance one has of convincing the audience and successfully proposing economic, social and political plans. And the better one utilizes and manages the popular discourse, the more the public thinks that person is capable of being a leader than can direct their society.

But with the Guna people, the logic is distinct. We do not just speak with our mouth and our discourse, we speak with all that we are, which involves all the senses. The leader, then, when dialoguing with another, relates to that other on a horizontal field because power does not make one of us more than another. One only has power when they serve the other and recognize that we need each other.

But for this to be real it must be realized in the praxis of power; in a dialogue which is lived through all the senses. When we build someone’s house, we all build it together. The work involves the whole body—the eye, skin, nose, ear, mouth. When a Guna youth sees his or her sagla (buwar/leader) work in the community with all the rest, without hierarchical pretensions, they are impacted by their model that speaks with their self and not just their words. Thus, their narratives take on life, inviting the little ones to understand that, “I cannot do this alone. I cannot carry the weight of the whole hut by myself.”

The Guna Revolutions

In our stories, our grandparents have taught us about Guna history, which in our language we call, “Ammar dadgan daniggid” which means “the path from which our grandparents come. Another way we refer to our history is, “Bab gan y Nan gan uilesat se daniggid”, or “the path from which our mothers and fathers come struggling and suffering.”

Each drop of blood that falls to the earth is a signal of the sacrifice made for that which we love. According to the way we are taught about the Guna Revolution, if our grandparents fought so that today we could be present and our nation would not die, then today we also should be willing to fight, even defending our land with our lives. Of our many revolutions, I would like to tell about the Revolution of 1925. When we speak of “The Guna Revolution” it is in reference to the bloody conflict of February 1925 in San Blas between the Gunas and the colonial police camped in of our communities.

The causes of the uprising were many and varied:

- The repression and violent abolition of our own ceremonies and rituals by the colonial police and Indigenous people who had been schooled Panama City.

- The bloody imposition of Western dress to replace our traditional mola.

- Raping and assaulting women.

- The unjust imprisonment of those who spoke against the police.

- The creation of dance clubs.

- The expropiation of land, theft, and invasion of comunal properties.

- The exploitation of our labor for the exclusive benefit of the colonial police.

- Murders and midnight assassinations of those who responded to the provocations of the police.

- The burning of the community of Niadub and the constant threat by the police to burn down other communities.

Each year this revolution is remembered. So that the generations behind us do not forget, we perform a festive commemoration. The narrative of this battle is shared in the form of theater.

Narrative through theater as a form of resistance

Each community in Guna Yala commemorates the Guna Revolution. One of the pedagogical methodologies used is drama and how each person learns has to do with the part they play in the drama. In many of the communities the youth are encouraged to participate at least once in their life. Each role is handed down from generation to generation so, if I am descended from someone who participated in the actual historical revolution, my role would be to reenact the part that my grandparents actually played in the the battle. This creates a greater connection to the dramatization in the person because you are reenacting something that is part of your own roots, thus, creating a character that is no longer fictional because it reminds each family of the sacrifice of their ancestors.

In this way our corporality also takes part in our remembrance and not just our mind. We occupy the same space with other bodies that are not alien to our suffering, celebration and expectations. We move in this same space not just from our knowledge but also from our being. The corporality of the celebration transcends philosophical abstraction and is rolled up in a philosophical reality in order to create the mystical event that is one people reliving their narrative through their bodies, which permits us to re-imagine and re-create new alternative political propositions to face the challenges that the Guna nation faces today. Theater is a mix of uncertainty and astonishment where the feelings of the spectators and the actors are united, turning the spectators into part of the show. So, for the Guna people this remembrance has made us reconstruct the events, update them, and continue teaching the newer generations that forgetting is prohibited. From there we continue forming generations who contribute to our socio-political organization with a commitment founded in our community values.

Conclusion:

To speak of narrative as political resistance among the Guna people of Panama is a topic that requires much more work to deepen our understanding. In this paper I have only commented in a general manner on the narratives that influence Guna politics and resistence. There is much yet to be explored, including the songs sung by the mothers and grandmothers, our medicinal songs, our dances, and much more. However, I think that it is important that we take the Guna people as a model in the political realm and that we continue to relate their narratives to their political action because there are concrete acts that validate this relationship.

In 1950 the Guna people’s territory was legally recognized and organized as a collective possession. With the passing of Law 16 of 1953 the judicial and administrative condition of the territory was definitively established and the borders where strengthened. Due to this legislation, the state of Panama accepted the organic charter as a legal indigenous form of government and the concept of comarca, or region, gained strength as a territory for autonomous indigenous government.

“We cannot let the story written by the wagas (non-indigenous people) about the events of 1925 continue to walk alone. If so, the same thing that happened to our ancestors in the invasion of Abya Yala could happen to us. Only what the wagas did, said and thought was left as truth. This all makes me very sad. When will we begin to work our own books? I will wait for you in Dadnaggwe Dubbir, before the month is over.”

Inakeliginya-Sagla Dummad of the general Guna congress. He was a deep knower of history, guna cultre and qualified translator of Bad Igala (The Way Towards God), recognized political leader, and source of the book “I saw it that way, they told it to me that way.”

Anexo

Estructura y organización social – politica de la Nación Guna

Onmagged dummad Sunmaggaled – El Congreso General Guna: tiene designado a tres Sagladummagan, es decir, Caciques Generales que tienen la representación oficial de la Comarca Gunayala, quienes son los portavoces ante el Estado panameño, organismos nacionales e internacionales.

¿Qué es el Congreso General Guna?

Es el máximo organismo político-administrativo, sus pronunciamientos y resoluciones son de cumplimiento obligatorio para todas las autoridades y comunidades de la comarca Gunayala. Se convoca dos veces al año.

El Congreso General Guna la integran las 49 comunidades que compone la Comarca Gunayala.

¿Cuáles son sus funciones más importantes?

Las funciones más importantes son:

De desarrollo: Analizar, elaborar, aprobar o improbar e implementar planes, programas y proyectos de desarrollo social, económico, cultural y político.

De sanciones:

* Aplicar sanciones a instituciones o personas que realicen sin autorización, proyectos, programas y planes que perjudiquen el orden social, cultural, religioso y económico.

* Sancionar a los Sagladummagan del Congreso General Guna, miembros de la Directiva del Congreso y de comisiones por extralimitación de sus funciones, por no cumplir las normas morales o las disposiciones del mismo Congreso. Sancionar a las comunidades y a las personas que infrinjan o no acaten las decisiones del Congreso.

De protección: Proteger y conservar los ecosistemas, bienes comunales y particulares. Establecer el uso racional de los recursos naturales. Defender y conservar la integridad territorial y la identidad del Pueblo Guna.

De Contactos. Realizar contactos con los órganos nacionales e internacionales o personas particulares.

De fortalecimiento Institucional: Exigir y evaluar informes y actividades de los Sagladummagan de las comisiones, representantes de entidades estatales, privadas y personas particulares. Ratificar a los Sagladummagan del Congreso General Guna. Nombrar comisiones de trabajo y de estudio. Fiscalizar los fondos de la comarca provenientes de cualquier fuente interna o externa. Sancionar y aprobar la ley fundamental, el estatuto de la comarca, su reglamento interno y todas las resoluciones.

Estructura de el Congreso General Guna

Nuestra máxima Institución política- administrativa está estructurada de la siguiente manera:

Congreso General Guna (Onmagged Sunmaggaled, compuesta por 49 comunidades)

– Junta Directiva del Congreso.

– Asesores

– Administración

– Secretaría Adjunta

– Administración de Arcos.

– Instituto de Kuna Yala, entidad técnica profesional).

– Comisiones (se crea de acuerdo a la conveniencia del Congreso)

Los Sagladummagan del Congreso General Guna actuales

Son los señores:

Sagla Inocencio Martínez de la comunidad de Aswemullu (Anassuguna).

Sagla Baglio Pérez de la comunidad de Assudub

Sagla Eriberto González de la comunidad de Niadub.

¿Qué relación tiene el Congreso General de la Cultura y el Congreso General Guna?

Se ha dicho que entre las dos instituciones hay dualidad de poder, y muchos se preguntan cuál de los dos tiene mayor jerarquía en la comarca Gunayala.

Entre ambas no hay dualidad de poder, ni uno está por encima del otro. Cada una tiene sus funciones definidas. Nuestro Congreso General de la Cultura se enmarca en el fortalecimiento de la cosmovisión, en tanto que nuestro Congreso General Guna- tiene que ver con la administración y política de la comarca.

Ejemplo, cuando se trata de rescatar y fortalecer algunas tecnologías, cantos sagrados etc., en extinción, la Máxima Autoridad Religiosa elabora planes, programas y proyectos para ese fin; en tanto cuando se desea elaborar propuestas políticas al gobierno o cualquier aspecto que implique desarrollo socio-económico el Congreso Político-Administrativo asume esa responsabilidad.

Hay momentos en que ambos Congresos coordinan trabajos concretos, por ejemplo cuando se aborda temas educativos, ya que éstos implican conocer y sistematizar prácticas culturales, planificar estrategias y técnicas educativas.

También los Congresos, a través de sus Juntas, se reúnen dos veces al año para evaluar el cumplimiento de las normas e intercambio de ideas para una asesoría mutua dentro del marco político- administrativo, cultural y religioso.

A pesar de que no haya jerarquía, es importante señalar que el Congreso General de la Cultura Kuna es el fundamento espiritual de la existencia del Congreso General Kuna, pero en las acciones ambos tienen sus competencias definidas.

¿Cómo fortalecer a los Congresos Generales?

En la comarca Gunayala, las comunidades tienen sus Congresos Locales, los cuales internamente son los máximos organismos; unidos forman el Congreso General de la Cultura o el Congreso General Guna.

Los Congresos Locales son espacios de reflexión colectiva, visibilizados en forma de cantos y ceremonias tradicionales o debates socio-políticos; y donde deben nacer propuestas de desarrollo para la comarca; y no esperar que la Junta de los Congresos realice tal afán. Aquellas mociones pueden ser expuestas por nuestras autoridades comunales a los Congresos Generales Gunas para su debate.

Por lo tanto como miembros de la comunidad debemos asistir a la casa del Congreso (Onmaggednega) y participar presentando propuestas, debatiendo ideas que sirvan para fortalecer y progresar la comunidad. Asimismo es nuestro deber velar que las decisiones y resoluciones de los Congreso locales y Generales se cumplan cabalmente.[11]

Dirigentes del congreso local:

Sagla: cabello, raíz, maestro, jefe de un trabajo comunal o un líder de una comunidad político-religiosa. Se elegí por consenso o votación popular, públicamente en el seno del congreso. Son elegidos con carácter vitalicio, pero pueden ser depuestos, si actúan en contra de los intereses colectivos, cuando no satisfacen las necesidades tanto morales como prácticas del pueblo entre otros temas.

El sahila debe ser perito en materia politico-religiosa( dominar los cantos metafóricos) haber dado buen ejemplo en su conducta, ser versado en la oratoria y poesía. Algunas de sus funciones presidir los temas políticos, económicos, sociales y culturales en la casa de congreso, dirigir las ceremonias religiosas como entonar cánticos metaforices-religiosos, ordenar la celebración de la asamblea a fin de aconsejar al pueblo, predicar la palabra de Dios. Afrontar toda clases de problemas. Participar de los congresos generales que se realizan a nivel de la comarca con delegados de la comunidad y se reúnen con otros saglas y delegados. Por lo general existe más de un sagla en la comunidad, en caso que el principal se enferme, o tena asuntos políticos que tratar en otra área

El argar:

Este termino hace referencia a la segunda autoridad, político-religiosa, tiene dos significados, traductor de las palabras metafóricas del sagla y en el otro costilla. El no solo interpreta la palabras metafóricas del sagla, si no que es un gran consejero, otras de sus roles son los siguientes: Consejero de los salgas, y del pueblo en relación a la ética,participa y acompaña a los saglas en sus misiones políticas y religiosos, asistir a los congresos general y tradicionales.

Sualibet: Literalmente quiere decir dueño de un palo o bastón, pueden haber 5 a 15. Los principales deberes, anunciar al pueblo cuando hay congreso, establecer el orden en las ceremonias, organizar la logística cuando hay congresos generales y la comunidad local es la anfitriona en relación a la hospitalidad, es el encargado de la seguridad y orden en el pueblo.[12]

[1] Buwar: Strong and resistant pole that stands vertically in the center of the hut. The number of buwars depends on the length of the hut. En defensa de la vida y su armonía, Aiban Wagua- Emiski- Pastoral, Second expanded edition 2011.

[2] Uusor: Refers to strong, shorter poles used to hold up the skeleton of the hut in the center and in the four corners of the Guna house. Ibid.

[3] Nagubir: Part of the Guna house. Pole that stretches across the width of the hut. We use it to tie the ropes of our hammocks .Ibid.

[4] Baggu: The poles that slant down from the highest point of the roof to help hold up the straw. Ibid.

[5] Dior: A short, relatively thin pole that is tied tightly to the end of the central pole in a horizontal position. Ibid.

[6] Magged: Several poles that make up the skeleton of the hut. Ibid.

[7] Saderbir: Part of the Guna hut. Ibid.

[8] Sargi: Bejuco. A strong vine-like climbing plant. Ibid.

[9] Aiban Wagua, pp 114-115

[10] Ibeorgun y Giggardiryai: Characters in Guna culture who were sent by Baba and Nana to teach our ancestors to organize themselves socially and politically.

[11] Congreso general guna, sobre su organización social y política, http://www.gunayala.org.pa/congreso_kuna.htm

[12] Arnulfo Prestán Simón, Organización social y política de Kuna Yala, Universidad de Panamá, departamento de historia, pp114-118